Serving Time in Connecticut

For Majewski and Carey, No Easy Road to Freedom

By Susanna Wood

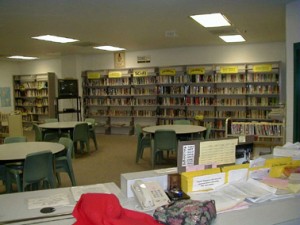

Inmates at MacDougall-Walker Correctional Institution in Suffield spend a good deal of each day in areas such as this typical cell block.

Ten years in jail is a long time. With two leap years that’s 3,652 days, 87,648 hours, 5,258,880 minutes. How does that time pass for inmates like Kyle Majewski and Matthew Carey, the two young men recently sentenced for a crime spree that ended with torching the Norfolk Curling Club in December, 2012?

How does someone come out the other side of a prison sentence and rejoin the world without ending up back inside? According to the Department of Corrections (DOC), after five years on the outside, 50 percent of ex-offenders will be serving new sentences.

Most of us have no real handle on what life in a Connecticut prison is like. We know someone else is in charge, telling inmates when to get up, when to eat, when to work, when to relax. But what else?

George Bronson, brother of Jody Bronson, Forest Manager of Great Mountain Forest, worked in the prison system for 20 years, the last seven as warden. “The first thing to remember is that it’s a community like any other,” he says, meaning that there are ways to behave that work better than others, that there are people just trying to get through and people who like to make trouble, and that there are temptations and also opportunities.

Bronson, now a college professor at Western New England University, also tells his criminal justice students, “Our worst day out here may be better than their best day inside.”

A check of the photographs on the DOC Web site of a typical facility reveals that, with the exception of the cell and the non-contact visiting room, the classrooms, library, dining area and gym have the look of a well-maintained vocational-technical high school. Unlike those grim buildings in movies about Alcatraz and Attica, the rooms look well-lit and clean. One aspect of prison life has improved significantly: the state’s inmate population has fallen to about 16,300 from an all time high of 19,894 in 2008.

Majewski and Carey are likely staying in a small room such as shown in this photo of a typical Connecticut jail cell.

So what is prison really like? As a newly convicted inmate serving a lengthy sentence, you arrive at McDougall Walker Correctional Institution near Windsor Locks for an assessment that includes mental and physical health, possible addiction problems, and potential for violence. Your clothes and all personal possessions are taken away for safe keeping except for sneakers (just black, white or gray allowed), and they will be checked for metal. You receive a toothbrush, toothpaste, soap, shampoo, a comb and two stamped envelopes per week to write friends and family.

Instead of a computer or a cell phone, there’s a landline phone, paper and a pencil. For at least the first six months you’ll have no physical contact with visitors. No visits are allowed on Christmas, Thanksgiving Day or any other state holiday. If a family member dies, you might be allowed to go to the funeral home for a viewing, but never to the funeral. If you smoke, you are quitting. Connecticut prisons are smoke free. You are certainly scared.

Days in prison are well-regulated and busy for a reason. As Bronson puts it, “a tired inmate is a good inmate.” Prisoners have to work, some in the laundry, the commissary or the kitchens. Others may have janitorial jobs or work on the prison grounds. One of the most prized jobs for those who with lower security ratings is to work with road crews picking up garbage along our highways, a chance to be outside in fresher air. Pay averages 75 cents per day which an inmate can use to buy items at the commissary, such as a set of watercolors ($2.21), gym shorts ($10.21), a can of yellow-fin tuna in spicy sauce ($1.86), or a light emitting diode (LED) television. ($193.70).

Inmates under 18 must go to school. In fact, Unified School District #1, which includes all the prisons, is the largest district in the state. About 800 General Education Diplomas (GED’s) are awarded each year in the prison system, as many as the rest of the state put together. On arrival, inmates test, on average, at sixth grade level in reading, math and writing. Only 25 percent have finished high school. Unfortunately, those with a diploma have little chance to go farther. Arrangements for Pell Grants to finance college correspondence courses are no longer in place and, with no Internet access, new, free college courses are beyond reach.

A few lucky inmates who end up at Cheshire Correctional Institute may be able to enroll in courses taught by Wesleyan University faculty. The program has recently been extended to the only women’s facility in the state, York Correctional Institute. Inmates at MacDougall can also apply for the program, and, if accepted, will be transferred to Cheshire. Inmates who participate in college programs have a 50 percent lower rate of recidivism.

Most facilities offer a wide variety of vocational programs. Courses at MacDougall-Walker include elder care, graphics and printing, upholstery, metalworking, carpentry and electronics.

Other programs focus on parenting skills and anger management, and inmates have access to various religious support groups and Alcoholics Anonymous.

With good behavior, Majewski and Carey will be eligible for parole after eight and a half years. Formal requests through the prison system for interviewing both inmates could not be completed in time for this article. How they will do when released will in large part depend on how they decide to do their time, but also on the support of family and friends, the luck and ability to get and keep a job, and the willingness of society to give them a second chance.