CCC Helped Relieve Depression in NW CT

Roosevelt’s Tree Army

By Veronica Burns

The familiar expression “Another day, another dollar” has its origins in a public work relief program from the 1930s. Paul Barten, executive director of Great Mountain Forest, recently gave a presentation at the Norfolk Library on the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the first component of Democratic president Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal. The goal of the CCC was twofold: the conservation of America’s natural resources, and employment for thousands of idle young men during the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl.

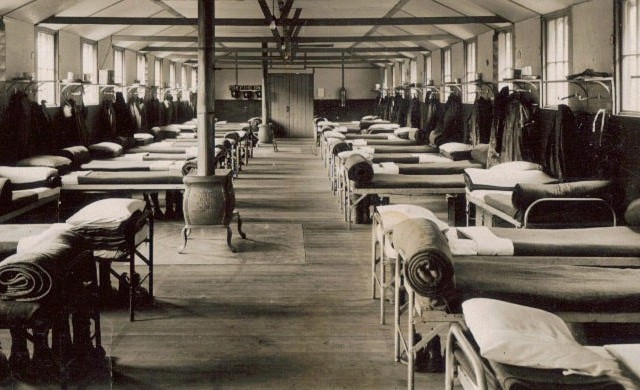

The state of Connecticut had 23 CCC camps, each with army-style barracks and a mess hall. One of those, in Burrville, was named Camp Wolcott, in honor of Norfolk resident Senator Frederick Walcott. Although a Republican, Walcott was a staunch supporter of Roosevelt’s CCC, probably because he was in favor of its emphasis on preserving natural resources.

In 1933 the senator toured Camp Walcott, and according to a contemporary article in the Hartford Journal, after the senator came upon a piano in the camp, “he struck at random several keys and winced. ‘I’ll send you a new piano,’ he told Lieut. R. H. Tiers, who conducted him about the camp.”

Music was likely a welcome diversion from the drudgery of the camps. Barten told his Norfolk audience that while the camps were not military operations, they were run by the army. It was thought that only the army could organize so many men in such a short time. The enrollees came from large cities, small towns and farms. They spent long days working in the nation’s publicly owned forests and parks, for which they were paid one dollar per eight-hour day and given five dollars spending money per month. In addition, twenty-five dollars was sent directly home to the enrollee’s family.

Jodie Bronson, a forester at Great Mountain Forest, recalls that his maternal grandfather Ernest Buchardt was a supervisor in the West Cornwall camp. The CCC hired “Local Experienced Men” (LEMs) as overseers in the various camps. Bronson says that since his grandfather was a machinist by trade and therefore skilled in “reading delicate instruments,” he became a road foreman. He supervised the surveying and laying out of new roads. Bronson adds that “my mother maintains that the CCC kept the family of eight alive.” He himself remembers playing at Camp Walcott when he was a child.

Another Norfolk resident, Ted Childs, a close friend of Senator Walcott, spent six months at a CCC camp in Vicksburg, Miss. His son Starling remembers his father describing the job as “supervising the multiple crews of young, poorly educated and out-of-work men, who felled the trees and hauled out the wood. He also tallied and sorted the daily output, seeing to the crews’ compensation and general safety.” Of immediate concern to his father was the “ high percentage of illiteracy among his CCC crews, and so he offered to teach both reading and writing in his tent by lamplight every evening. One particular young man went from near total illiteracy to high school equivalency, thanks to Dad’s help. Much later he went on to college, assisted financially by Dad, who stayed in touch with him. He eventually earned his master’s in civil engineering.” The former CCC enrollee brought his family and grandchildren to visit Norfolk one summer and repaid the loans that had helped him get an education.

By the time the CCC program ended in 1942, more than 2.5 million men had served. They planted over three billion trees, combated soil erosion and forest fires, and built roads and bridges and national park structures, some of which, mostly in the South and West, are still standing today.

Photo courtesy of Black Bass Antiques.