It’s Only Natural, March 2015

Looking for Antlers in the Winter Woods

By Wiley Wood

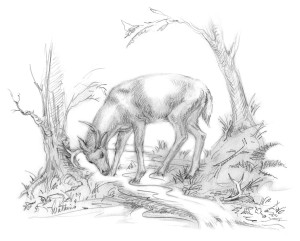

Deer hunting season ends in November, but a new season starts in February: shed hunting. It doesn’t require a gun or a license from the state. The point is to find antlers in the woods that have been shed recently by white-tail bucks.

I learned this on a March day when, emerging onto a trail in the forest, I encountered a man standing somewhat uncertainly at the next bend. “Are you the landowner here?” he called. I said I wasn’t, and he approached, explaining that he was looking for antlers in the shallow snow on the forest floor.

The bucks, who rut in the fall, shed their antlers in January and February. Shed hunters comb the woods as soon as the heaviest snows subside, following deer trails, along which most of the antlers lie. The trick is to find them before the mice do. Small rodents nibble on them for their potassium and calcium, and our biggest rodent, the porcupine, can reputedly chew through an antler in a single day.

“You have to throw your eyes out ahead of you,” the man said, “the way you do when you’re hunting.” He suggested that charcoal pits are particularly productive, those bare, circular platforms in the woods where an earlier generation made charcoal for the iron foundries. He had once found two sets of antlers within a few hundred yards of each other, one at a charcoal pit and the other along a game trail leading to it.With this advice in mind, I have more than once veered off a snowy trail to follow a well-traveled deer path, walking around the deadfalls that the deer slip under, struggling through thickets of laurel, climbing to the shoulder of a ridge where deer had slept under a canopy of hemlocks, the imprints of their curled bodies melted into the snow, the glazed surface sometimes retaining the exact trace of a leg they had tucked under them.

Or the trails may traverse a slope downward, lead to a valley bottom, to frozen marshes, where the trampled snow and widely scattered droppings show that deer have yarded up there longer than a night.

But for all my scouring of these sites, my watchful retracing of deer trails from one drainage to another, I have never found antlers as a result of purposeful activity—always by chance.

I decided to consult more expert shed hunters. Bill Couch, whose excellent collection of antlers I’d heard of, has been hunting sheds in early spring for several years. He suggests streambeds as a place to look particularly carefully. The buck jumps across and the motion can dislodge an antler. Couch also says the buck will often walk somewhat off the trail, 5 or 10 yards to either side of it. And he has found antlers wedged against fallen logs, suggesting that the bucks butt against them to knock an antler loose.

The winter woods are lovely, and no other reason is needed to wander through them. But if you go looking for antlers, you will gain a more detailed sense of the movement of animals through the forest—and see things you wouldn’t otherwise.