Report From the Real Russia

Former NPR correspondent Anne Garrels publishes book on the Russian heartland

By Lindsey Pizzica Rotolo

“Those were the very best of days,” says Anne Garrels of the early 1990s when her husband, Vint Lawrence, went to Russia to visit her for six weeks every three months. “He couldn’t work on his drawings because there was no FedEx, so we would go out to the far east, travel, laugh a lot.”

That was 1993, when Garrels was covering the aftermath of the dissolution of the Soviet Union for National Public Radio (NPR). It had been over a decade since her last extended stay in that part of the world. Her first trip to the Soviet Union was back in 1979, and almost by chance. She filled in for someone at World News Tonight while “a lowly researcher at ABC,” and impressed her boss enough that he urged her to go cover Russia. “They thought my Russian was better than it actually was,” says Garrels. She went to Moscow for three years, as bureau chief, and stayed until she was expelled in 1982.

The journalist’s passion for Russia began as a student at Middlebury College. An advisor suggested she take Russian. “He improbably argued it would be a good complement to a pre‐med curriculum, correctly suspecting I had as much of a scientific mind as a chipmunk,” says Garrels. She transferred to Harvard’s Radcliffe College after her sophomore year at Middlebury and graduated in 1972 with a double major in English and Russian.

Her first job out of college was working for a publisher in England. There was a wave of dissident books coming out of Russia in the mid‐1970s, so Garrels was well positioned, but the call of a life in broadcasting was stronger. She moved back to the states in 1975 and began a career with ABC that lasted until 1985. Then, she served as NBC’s correspondent at the state department for three years before going to work for NPR in 1988. She retired in 2012.

While Garrels may be best known for her live reporting from Baghdad during and after the 2003 Iraq War, her true passion remained 2,500 miles to the northwest—in Chelyabinsk, Russia. She travelled back to Russia from Iraq to fill in for fellow journalists from time‐to‐time, and covered Moscow for NPR in the 2000s. “I was floored by what I read in The New York Times a few years ago. They made it sound like revolts were taking place everywhere, but that was just in Moscow. The rest of Russia isn’t Moscow.”

That point was made clear in Garrels’ recently published book, “Putin Country: A Journey into the Real Russia,” which focuses on Chelyabinsk, a remote, industrial city 1,000 miles due east of the capital. Chelyabinsk, and its inhabitants, make an excellent lens from which to view a country that has come so far, yet is slipping back in time in so many ways. “What I really wanted people to understand is what Russians have gone through since the breakup,” says Garrels.

She certainly achieved that goal. The book’s chapters are each dedicated to a different segment of the population—business owners, magazine editors, factory workers, homosexuals, alcoholics and addicts, parents of children with emotional, behavioral or developmental issues, teachers, doctors, former soldiers, prisoners, the devout (of various religions), human rights activists, forensic pathologists, journalists and nuclear workers.

The relationships Garrels cultivated in Chelyabinsk during her numerous visits between 1993 and 2015 are clearly deep and intense. “Putin Country” reveals how trusted and respected the award winning journalist is in this region, evidenced by the wealth of knowledge shared (not to mention the number of intimate family events she attended). But some of those relationships have fizzled, or at least been strained as the result of Putin’s crack down on the “puppets of the west,” (as he calls American journalists and politicians).

As current tensions with Russia are reaching pre‐Gorbachev levels, it’s hard for Garrels to have much hope of continuing these relationships. “People who have a lot to lose are not as enthusiastic to talk to me as they were even a few years ago,” says Garrels. “Thank God for Skype though—most of my friends still feel they can communicate freely that way.”

Garrels acknowledges that some things have improved in Russia, like education, parents’ rights and the overall standard of living, but the current social and political climates are “nothing like what the hopes were in the 1990s.” While she savors the memory of Russia in 1993 mostly because of wonderful reminiscences of her recently deceased husband, many Russians today look back on the early 1990s “with horror, and appear willing to sacrifice certain freedoms for stability and a sense of national pride.”

“Putin Country: A Journey into the Real Russia” is available on Amazon and at bookstores. An audio version, in Garrels’ voice, is also available for purchase.

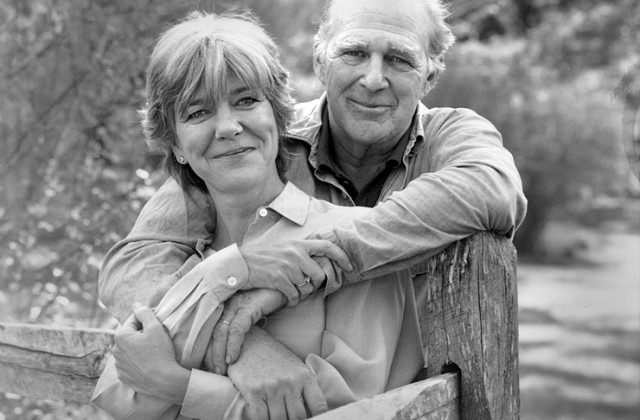

Photo of foreign correspondent and author Anne Garrels with her husband at home in 2003 by Christopher Little.