Victor Leger’s Vivid Landscapes Capture Berkshire Light

February Exhibit at the Library

By Gordon Anderson

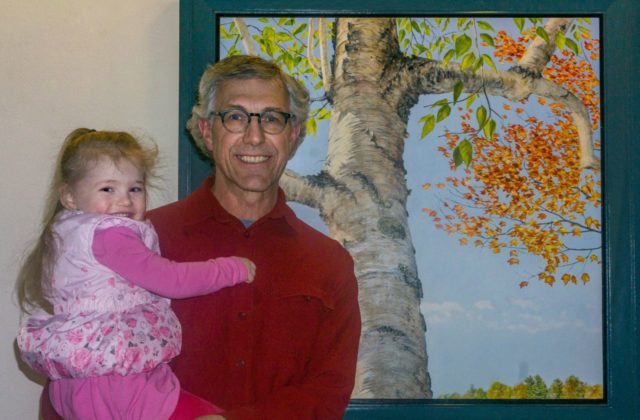

Photo by C. J. Sosna

After Victor Leger gave his acceptance speech as the 2010 Torrington public school Teacher of the Year, he performed a clog dance to the Hot Rods’ version of “Foggy Mountain Breakdown.” This exuberance is reflected in Leger’s art. Filled with sudden joy and the indescribable angles of light peculiar to the Berkshires, his paintings will be on display at the Norfolk Library through the month of February.

Tall, bespectacled and clad in flannel, Leger led me on a very cold and clear January afternoon up the stairs of his garage to his sunlit, pristine studio. The smell of oil paint and the sharp light of winter immediately struck me as I was greeted by a trompe l’oeil painting of a window looking out at a birch tree in the fall, its leaves bright and glowing in sunlight.

I am suddenly surrounded by these lovely depictions of trees, so real and vibrant that I am momentarily speechless. Leger tells me that he sees his work as three-dimensional, that he feels he is a sculptor in paint—and it’s true. These images stretch out their gnarled, lichen-laden branches, beckoning us, offering us a glimpse of a particular moment, a sense of reality caught in a breath.

As a teenager in Hartford, Leger showed so much talent that he won a spot in the magnet school of fine arts that met at the Wadsworth Atheneum. There he and other young artists learned about paint and framing, light and contour, as well as art history. They painted from photographs, from objects arranged on a table, en plein air and, most remarkably for teenagers at that time, from live models. These experiences, combined with his natural ability, produced a student with so much skill that he won a full ride at the Pratt Institute of Art in Brooklyn.

Leger also brought his love of woodworking and carpentry to bear on his painting. After graduating from Pratt, he made a living following in the footsteps of his father and grandfather, both French-Canadian woodworkers. Today, he makes all of his own frames, and he says that they are as much a part of his art as the paintings themselves. He uses basswood, which is especially light, and he finishes each with an acrylic lacquer, in a color that he has custom-made. Unusually, he adds a thin black strip to the inside of each frame. This has the unexpected effect of bringing extra light to his paintings, emphasizing the sense of looking through a window into the outdoors.

Leger calls his current work “skyscapes,” as opposed to landscapes, and he explains that the distinguishing factor is the lack of horizon in the composition. And, in fact, despite the apparent focal point of these paintings—the lovely, light-filled trees, their leaves and bark—the sky could be said to be the subject of each canvas. I asked him about his influences, and he immediately responded, “the later works of Maxfield Parrish,” and brought out a book to show me. Parrish’s paintings have a striking quality of light and color that call to mind the sun on Haystack Mountain and are strongly evocative of what the poet Hayden Carruth called “Norfolk light.” But while Parrish’s landscapes are largely imaginary, Leger’s have a hyperrealism tinged with a startling familiarity: stone walls, trees in snow, trees in spring, in full summer, in bright autumn. I found myself saying, “I know that place. I’ve looked out that window.”

We leave his studio and go to his house, where he shows me more of his work, as well as that of his wife, a nationally recognized artist and quilter. Her pieces are hung throughout their home, and they are beautiful, vivid and skillfully crafted. In the summer of 2015, both Leger and his wife were selected to be artists in residence at Acadia National Park.

I ask Leger how long he has been painting landscapes. His early work had been primarily landscapes as well, he says, but for many years he was heavily influenced by the collages and abstract expressionism of Robert Rauschenberg. As he evolved as an artist, he found himself incorporating more natural scenes into the paintings, and eventually they grew more prominent in the compositions. However, he only made the purposeful shift toward full-bore realism shortly after September 11, 2001. The fall of the World Trade Center Towers left him reeling, and he realized that what people needed was “a salve, something to calm their nerves.” He read a study reporting that when landscape paintings are hung in health-care settings, patients heal more quickly. Feeling that his own work had that power, he began to experiment with returning to his first subject, nature.

Leger’s land and skyscapes are not only lovely, they are also dramatic and strikingly dynamic. There’s a quality of immediacy and a sharpness in the contrast of colors and light that takes one’s breath away. In these paintings, the window is open; the viewer feels called to walk in the meadows and under the trees, rather than to curl up by the fire. These are complex, painterly works that energize rather than comfort. Leger’s canvases are timely reminders of the impact of natural beauty on the human spirit.