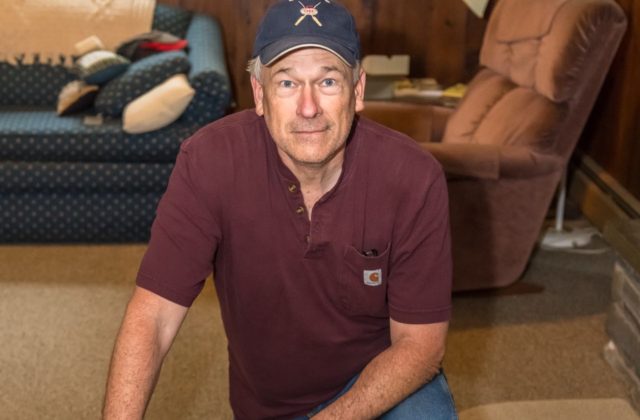

Joe Hurst: “We Need to Pull Together”

By Gordon Anderson

Photo by Savage Frieze

Joe Hurst lives on Mountain Road, in the last house before the road is absorbed into Great Mountain Forest. He says that every day when he turns the corner heading home, he is overcome with gratitude and delight at the miraculous quality of his life, or as he puts it numerous times during our talk, at how blessed he feels.

Born the last child to a strong Irish Catholic family on Emerson Street, he began his life one day before his mother died, leaving his father alone with seven children under the age of nine. “Thank goodness my dad never liked to drink,” Hurst says. “It was a hard life, though I didn’t know any better.”

The roots that nurture him are unabashedly in Norfolk. He is frank in his passion for the town. “Middle America,” he says, “that’s who I am. And I have three great loves in my life: my wife, my town and cutting stones.” His wife, Elisa, has been at his side throughout much of his 63 years, sharing his life with its challenges and joys, its blessings and sorrows.

In his late teens, Hurst was hitchhiking to Hartford to participate in a three-year civil engineering program while at the same time trying to make ends meet. The strain proved unsustainable, and Hurst turned to cutting local stones as a way of relaxing and exploring his creative bent. It didn’t pay the bills, though, and he began working for Jim Tallon at his lumber company, which was then located in Norfolk. With two years of engineering under his belt, the young Hurst fell in love with site mathematics, and Tallon, impressed, sent him to UMass to learn hardwood lumber grading. He loved the lumber business, but by then newly married, he was forced by the realities of economics to leave Tallon and embark on another path.

With the purchase of the Hawk Ridge Pub (now the Wood Creek Bar and Grill) in 1980, Joe and Elisa Hurst became a part of the Norfolk community. They took what had been, as Joe describes it, “kind of a dive” and opened it up to families coming for dinner, locals stopping in for lunch, and a generous mix of laborers, weekenders, townies and summer visitors hanging out at the bar for drinks with friends. Elisa plied her trade as a hairdresser, while Joe tended to his greater Norfolk family. He was 24 years old and his father called him “a damn fool” for taking the risk of buying a restaurant. When he sold the pub 12 years later, as a solid success, he was 36—and his father called him “a damn fool” for letting it go.

Hurst recalls that time as a “young person’s game,” and though he refers to the experience as another blessing, it took a toll on his energy. After a restorative trip to Niagara Falls, the Hursts returned to their split-level house on Mountain Road to consider their next venture. He began working with David and Dominique Low as their estate manager and traveled extensively around the United States. The long absences, and his deep involvement with the Lows’ Husky Meadows Farm, only sharpened his awareness of the loveliness of his home town. Eventually, though he loved the work and the satisfaction of watching Husky Meadows develop and thrive, he realized that he was in need of a deeper reconnection, a regrounding, with the town.

Then the Norfolk Curling Club burned to the ground.

Elisabeth Childs was an influential person in Hurst’s life, and the curling club was her legacy to the community. Hurst felt that that rebuilding it was critical to the health of the town. “Give now!” he said to everyone he met. “Everyone has skin in this game—give to your town somehow!” He says that he was suddenly struck by how fragile and beautiful the town is. There is a true wealth of resources, both natural and historical, but the sense of connectedness and responsibility for maintaining the integrity of those resources cannot be sustained if the residents aren’t personally invested in the process.

Hurst feels that the rebuilding of the Norfolk Curling Club was the beginning of the current Norfolk renaissance. “If we can do that, we can do anything; we can do Rails to Trails, we can do City Meadow.” Hurst is now the president of the Norfolk Foundation, which is playing a significant role in the town’s renewal.

He lists some of the vibrant attractions of Norfolk, including the Battell Stoeckel estate; Yale and its associated summer concert, art, and forestry programs; the Historical Society; and the library. “Those of us who live here are blessed,” he says. He believes that Middle Americans are the hope of the town, and he hopes a combination of their can-do attitude and a commitment to community volunteerism will continue to drive Norfolk forward. “We need to pull together,” he says again.

Pulling together includes supporting Botelle Elementary School, and Hurst is at almost every meeting of the school board, talking one-on-one with the principal, the board chairwoman, and parents, teachers, the superintendent and members of the Board of Finance. Without a vital and dynamic school at its center, Hurst believes that Norfolk as a town will slip into inertia, and he is working hard to keep that from happening.

Hurst’s positive spirit, coupled with his lifelong interest in stonecutting, has led him to create a new company, On The Rocks. Using his gemstones, he and a friend have built intricate bronze, stainless steel or aluminum tables with wooden inlay around the inside of the edges. Shining blocks of polished stone fit perfectly into the tabletop and can be interchanged with different colored stones to match moods or seasons.

We go downstairs to look at a small sampling of his stone collection, and he shows me stones from Argentina and Brazil, from Afghanistan and Madagascar, from Arizona and Oregon. Rinsed and shining, the stones are beautiful, each unique, deep blue and green, amber and ocher and purple. He opens a folded paper. “These are Herkimer diamonds. They are quartz crystals from Herkimer, N.Y., and you can just take them right out of the ground.” These are the clearest quartz I’ve ever seen and are 550 million years old.

“Heat and pressure made these,” he says. “All these stones are the result of enormous heat and pressure.” Hurst’s optimism and energy seem also to be the result of enormous pressure, and indeed, he says that it often takes periods of stress to produce meaningful change and resolution. Over the years, he has been working on shaping the gem that is Norfolk, hoping to polish and protect its loveliness for the townspeople and their children’s children.

An studio open house displaying Joe Hurst’s stonework will be held at the Norfolk Hub on June 22 from noon to 2 p.m.