Masks, Mistakes and Progress on Covid-19

By Richard Kessin

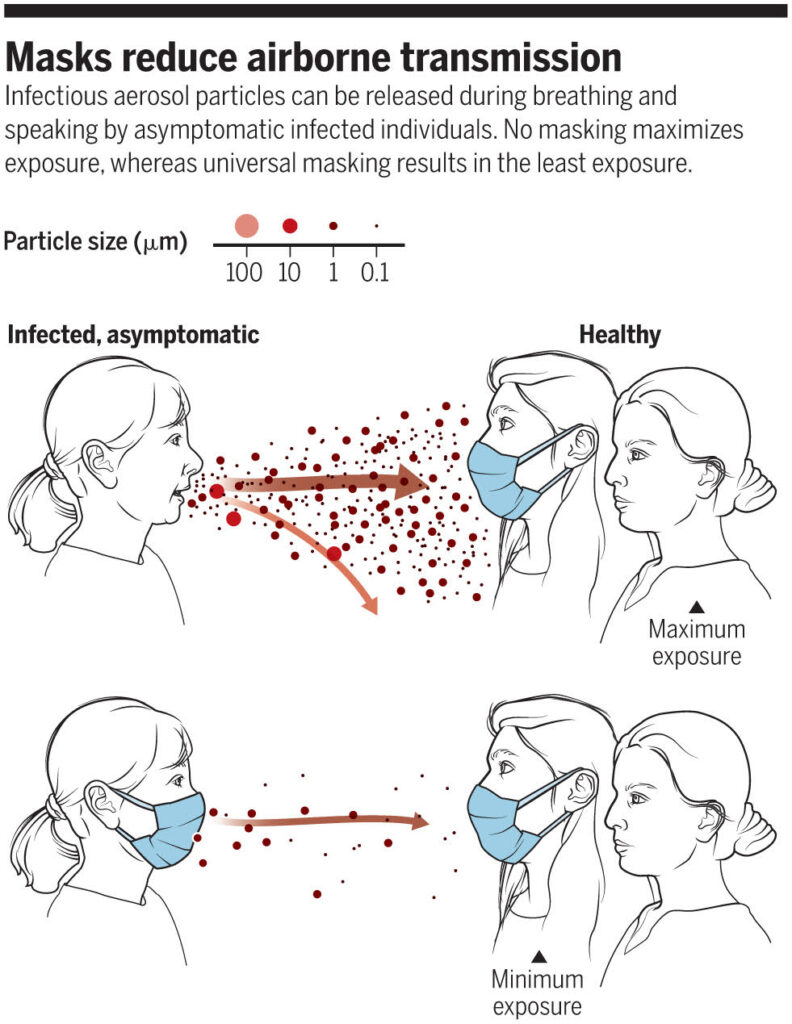

We are currently arguing about masks and disease prevention. Virologists and others (including me) thought that because the Covid-19 virus is so small, it would pass through a normal surgical mask. But masks are useful because viruses come packaged in large respiratory droplets that are blocked by the mask, and they also keep you from touching your face.

A review on airborne transmissionby Drs. Kimberly Prather, Chia C. Wang and Robert T. Schooley was published recently in the journal Science. The authors distinguish large infectious particles and small ones—both emerge from a cough or just the breath of an asymptomatic individual. The largest droplets, a tenth of a millimeter in diameter, could contain millions of viruses, but they sink within the now famous six feet. These respiratory droplets contaminate surfaces, where virus particles may remain infectious.

The small particles are about 1 micrometer in diameter and could contain up to 1,000 viruses. These particles float in the air and accumulate in rooms. Minute floating particles, or aerosols, have a long history as a nemesis in microbiology. Louis Pasteur, who saw them in bright beams of light in dark rooms, knew in 1863 that they were a source of contamination.

Once a particle containing viruses enters cells deep within the lung or infects cells in the sinuses and throat, new viruses can be made immediately—lots of them. The first patient in Wuhan had hundreds of millions of viruses in about five drops of fluid extracted from a site deep in his lung.

So wear a good mask and keep your distance. Clean your hands and the surfaces you touch. For the scientific paper that supports these thoughts, enter DOI 10.1126/science.abc6197 into any search engine. The information is readable and free to download. DOI, by the way, stands for Digital Object Indicator—not poetic perhaps, but it gets you to the evidence, which is all we have until the emergence of more active measures.

Where are we with vaccines and other therapies? All vaccines, drug treatments or other therapies pass through clinical trials, which are a complex arena with many rules to protect volunteers and patients. Clinical trials have three stages. The first, which uses only a few volunteers, is to make sure a vaccine or drug is safe and to establish a dose that provokes, in the case of a vaccine, an immune response. The second phase treats more people. It looks for adverse reactions and the activation of the immune system, but not yet efficacy. The third phase tests protection from infection and requires thousands of patients or volunteers of all ages and ethnicities to get statistically significant answers. Neither physicians nor patients know whether a specific injection contains the vaccine or a placebo. Well-designed clinical trials are the most critical part of solving Covid-19.

After a late start, the British are making progress. They have the advantage of the National Health Service and its hundreds of hospitals, one of which recently saved the life of Prime Minister Boris Johnson. The NHS uses one simple clinical trial protocol and reporting system for all its hospitals, making it easier to enroll patients than in other large trials. The British system is called RECOVERY (Randomised Evaluation of Covid-19 Therapy) and has already yielded results.

The NHS proved the value of dexamethasone, an anti-inflammatory steroid drug used for Covid-19 patients on ventilators. Other data showed that hydroxychloroquine provides no benefit. Several drugs that are useful against HIV and might have worked against SARS-CoV-2 did not help. According to Science magazine reporter Kai Kupferschmidt, these three results changed the standard treatment of Covid-19 over a few weeks.

Interferon, which affects inflammation, may help and is now being tested in various formulations. Like many drugs, it depends on when in the course of the infection it is given. Monoclonal antibodies that bind to the SARS-CoV-2 virus and neutralize it are being tested, either for treatment or prevention.

Finally, this week the data from phase 1 and 2 trials of two vaccine candidates were released—one by a company called Moderna, and the other by the vaccine team at Oxford University. Both provoke a robust immune response in healthy volunteers. Both stimulated the production of circulating antibodies by B cells. They also induced T cells that recognize infected human cells and kill them. The responses took two to four weeks. The two vaccines employ different mechanisms to provoke the human immune response, and both will probably begin large phase 3 trials in the next month or two.

There are many other candidates, and we will follow their progress, but the important part of this process is the excellence and size of the clinical trials, not only the nature of the vaccine.