How a Norfolk Man Came to be Chased by Bears in the Ozarks

A Look Into Norfolk’s Past

Text by Andra Moss

Photo Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society

Grand adventures are often thought to be reserved for the young. One early Norfolk resident, however, embarked at the somewhat ripe age of 38 on an epic journey into the wilds of the Missouri Territory. His traveling companion became a hero in that state’s history, yet Levi Pettibone remains but a footnote. It all comes down, one supposes, to who tells the tale.

Levi Pettibone was the seventh of eleven children born to Col. Giles Pettibone and Margaret (Holcomb) Pettibone, both originally of Simsbury. (Levi Pettibone’s uncle, Jonathan Pettibone Jr., built the Pettibone Tavern in 1803 that still stands today as Abigail’s Grille on Hartford Road in Simsbury.) When they moved in 1758 to Norfolk to start their family, the Pettibones lived in a British colony and a town that had not yet been officially incorporated. The Norfolk home of Col. Pettibone and his family is one of the town’s oldest and stands proudly just above the Catholic Church on North Street.

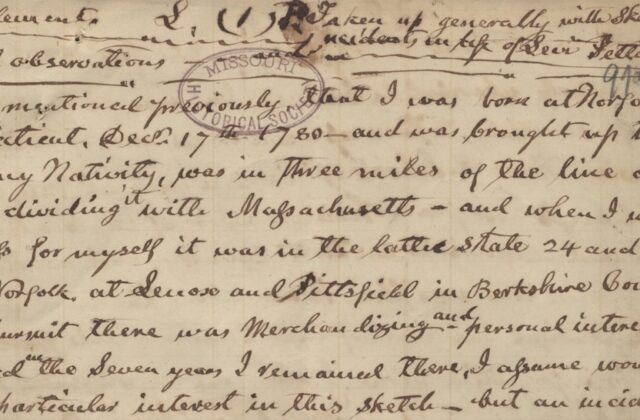

Incredibly, Levi Pettibone left a handwritten autobiography, now in the collection of the Missouri Historical Society, which clarifies that he was born on Dec. 17, 1780, in Granby, Conn., where his mother had relatives. Mother and infant soon returned to Norfolk, where Pettibone was baptized in Jan. 1781 and grew up in an active and prominent household, his father a respected town and state leader.

No records document his youth in Norfolk, but Levi Pettibone wrote that, “when I went into business for myself it was…30 miles from Norfolk at…Pittsfield in Berkshire County – my pursuit there was Merchandizing – and personal interests that occurred in the seven years I remained there I assure would not be of particular interest in this sketch…” Perhaps that is why he chose, in 1818, to start fresh.

Pettibone was close to his younger brother, Rufus, who was practicing law in Vernon, New York in the spring of 1818. The two brothers decided that opportunities were ripe in the new Missouri Territory and, joined by a friend of Levi’s, Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, packed up Rufus’ home, wife and three small children and floated 300 miles by raft down the Allegheny River from Olean, NY to Pittsburg, Penn. and then overland to St. Louis.

It was in Missouri that the adventure really began. Schoolcraft, who at age 25 had some training and a keen interest in geology (Pettibone would playfully call him in a letter “a man who can see much farther into millstones, etc., than other people”) had the inspiration to explore the mostly unsettled region now called the Ozarks for its mineral potential—and perhaps make a little money in the sharing of this information. He invited his friend Pettibone to join him for this unmapped winter journey of indeterminate length. Pettibone was all in.

On Nov. 6, 1818, the two departed Potosi, Missouri “armed with guns, and clothed and equipped in the manner of the hunter” and leading a horse named Butcher carrying their supplies. They would be gone for three months and cover 900 miles on their circular trek.

As they left, a veteran settler noted, “I reckon, stranger, you have not been used much to travelling in the woods.”

From Schoolcraft’s daily journal, published under the title, “Journal of a Tour into the Interior of Missouri and Arkansaw,” we learn that their progress was slower than anticipated. Ten days in, they feel sure they have lost their way and reroute further south. On Nov. 19, Schoolcraft records Pettibone spraining his ankle in a chase with four bears. That same day, poor Butcher takes a bad fall down a ridge. The downward spiral continues when, two days later, their food, shot and supplies are mostly ruined during a river crossing. Perhaps one of the lowest days might have been Nov. 27, when, their provisions exhausted, they leave Butcher behind and set out to find a hunting cabin that they hope exists ahead. Nov. 28 holds the short entry: “Ate acorns for supper.”

Their luck changes, however, on Nov. 30. Schoolcraft writes that they “met a man on horseback. He was the first human we had encountered for 20 days, and I do not know when I have received a greater pleasure at the sight of a man…” Elated, they follow their new best friend “to a hunter’s house on Bennett’s Bayou.”

From this point on, the duo regularly receives supplies (and directions) from hunters, trappers and intrepid settler families along their way. The valiant Butcher gets them through a swamp on Dec. 6 and Pettibone and Schoolcraft advance, marveling at the prairies that are “covered by a coarse wild grass, which attains so great a height that it completely hides a man on horseback in riding through it.”

A final hurdle comes on Jan. 12 when they must switch to canoe and run the rapids of the Bull Shoals section of the White River. As Schoolcraft recounts, “Here the river has a fall of 15 or 20 feet in the distance of half-a-mile and stands full of rugged calcareous rocks, among which the water foams and rushes with astonishing velocity and incessant noise…We found our canoe drawn rapidly into the suction of the falls. In a few moments, notwithstanding every effort to keep our barque headed downwards, the conflicting eddies drove us against a rock, and we were instantly thrown broadside upon the rugged peaks…”

Whether by skill or luck, the travelers do safely make their way home, arriving full circle at Potosi on Feb. 4, 1819.

Schoolcraft’s book was published in London in 1821, earning him a lasting place in the history of the exploration of Arkansas and Missouri. It should be noted that in its over 100 pages chronicling hundreds of miles traveled together, Schoolcraft mentions Pettibone in fewer than four lines of text. He does once say of Levi Pettibone, “He stood stoutly by me, and was a reliable man who could be counted upon in all weathers to do his part willingly.” Perhaps he actually meant this praise for dear Butcher, traded for a canoe?

Levi Pettibone remained in Missouri and was for years circuit clerk and county treasurer of Pike County. He married Martha Lowrey Rouse of Granby, Conn. on June 14, 1831. They had two daughters and also raised their niece, Maria Pettibone, who was just 12 when her father Rufus died. In Chrissy’s “History of Norfolk”, it is recalled that “Levi Pettibone retained the powers of his mind and body all his life. He was an unusually fine penman and bookkeeper; at the age of 90 he was hired to open a set of books for a bank, and at the age of 94 he was still working four hours daily as bookkeeper for a shoe store.”

Levi Pettibone died on June 24, 1881, at the age of 101, St. Louis’ oldest resident and one of Norfolk’s most daring explorers.