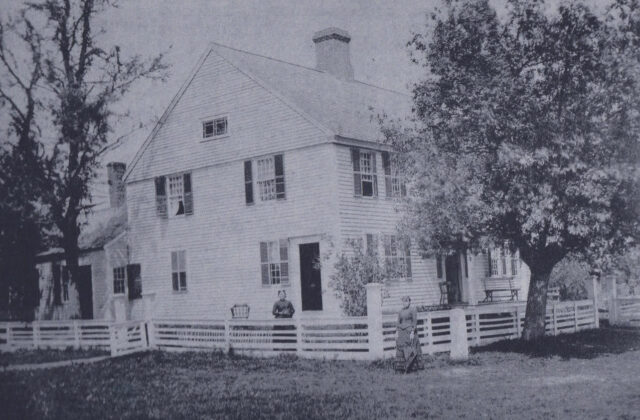

The Wilcox Tavern House

This Old Norfolk House

Text By Michael Selleck

Photo Courtesy of the Norfolk Historical Society

It’s probably not a good idea to fall in love with a house, but that’s exactly what I did when I first visited the Wilcox Tavern in 2016. I was searching for an 18th-century house because I was looking for a project—I had no idea what that entailed! I wanted a home that had a past, in a community that had both history and a future. I had grown up in a small town, so when I got to Norfolk, I felt like I was home. The Wilcox Tavern met all the requirements for both a restoration and a renovation.

Ezekiel Willcocks (Wilcox) was born in Simsbury, Conn., in 1735, the son of Amos Willcocks. He was an ensign (2nd lieutenant) in the Colonial Army and in Colonel Giles Pettibone’s company during the French and Indian War. In August of 1757, they went to Fort Edward at Lake George during the fall of Fort William Henry, an event memorialized by James Fenimore Cooper in “The Last of the Mohicans.”

Following the war, Ezekiel and some of his brothers came to Norfolk, where land was being offered to settlers in lots. On June 21, 1763, Ezekiel purchased Lot 37 of 50 acres on Beech Flats for 100 pounds, 10 shillings ($28,000 today) from Captain Daniel Lawrence. Even though Wilcox went on to purchase other property in the area, early colonial maps indicate that the Lot 37 is where my house stands today. Sadly, there is no record of when the house was built, but given the timeline of other events in Ezekiel’s life, it was probably around 1765.

His wife-to-be, Rosanna Pettibone, was the sister of Colonel Pettibone, one of the early landowners in Norfolk. Perhaps Rosanna and Ezekiel met in Simsbury or when Ezekiel was in her brother’s army. Whether they were already engaged when Ezekiel set out for Norfolk is unknown, but they married in 1764 when he was 29 and she was 26, which was rather old for marriage at that time.

There are two stories about Rosanna traveling to Norfolk from her home in Simsbury. In one, according to “The History of Norfolk,” she set out alone and became lost en route, but she kept on and even spent a night alone in the woods. Another tells how she came to purchase her wedding dress. Rosanna had woven a piece of checked linen, which she intended to sell to a man in Canaan. She departed again from Simsbury for Norfolk, this time on horseback and in the company of a Benjamin Mills and his wife. The roads were little more than a trail or even a bridle path through the dense greenwoods. They rode from Simsbury down to Torrington through Winchester, coming north to the southern parts of Norfolk. After several days of travel, they finally reached her brother’s home in Norfolk, and he accompanied her to sell her cloth so that she could buy her wedding dress.

The Wilcox family settled into Norfolk, their home a large two-story post and beam colonial. Their first child, Charlotte, was born in 1766, and a second daughter, Rosanna, in 1769. There is record that a third child, Ezekiel, was baptized and buried in 1771. Another son, also named Ezekiel, was baptized on Jan. 31, 1773.

Recorded history reports a fulfilling life in colonial Norfolk. Ezekiel became a town selectman, and they were members of the church, where he was named first chorister. But tragedy struck on June 23, 1774, when Ezekiel was just 39 years old. As a town selectman, it was his responsibility to make sure that families were put under quarantine during a smallpox outbreak. After visiting the home of Abner Beach, he was exposed to the virus and died at home. Ezekiel was only the sixth head of a household to die in Norfolk.

Rosanna Wilcox was 36 at the time of her husband’s death and the mother of three children, her youngest only a toddler. Sometime in 1775, the board of selectmen gave approval for the widow Wilcox to run a tavern, or a public house, from her home. Taverns were a big part of colonial life, a necessary resting place for stagecoaches where weary travelers could get a warm meal and a bed for the night and a barn for their horses. Since Norfolk was located on what was then called the Hartford to Albany Turnpike, there were many taverns located in town.

One story has it that once John Jay, the first chief justice of the United States, visited here. Apparently, he had stopped to rest on his way from Hartford to Albany, maybe to have a meal and a bed. But for some reason, he did not stay, and he wrote in his journal that the Wilcox Tavern was a “bad house.” It has been suggested that the widow Wilcox may have been up to something the chief justice did not approve of. Whatever the cause of that incident, Rosanna Wilcox was adored by her children, who referred to her as “our honorable mother” in her estate papers.

All three of the Wilcox children married locally and went on to have families of their own. The Wilcox daughters are noted in local history for “loveliness of character and great personal beauty.” They were called “the flowers of Norfolk.” Charlotte married Colonel Noah Amherst Phelps and lived in Simsbury. Rosanna married Eden Mills, and they and their 10 children stayed in Norfolk. Eden Mills was very active in church and town activities. Ezekiel married Olive Welch, one of the daughters of Hopestill Welch, but after his mother died, he and his wife followed other members of the Welch family to Shalesville, Ohio. Both Eden Mills and Ezekiel Wilcox grace the list of names that supported and contributed to the new meeting house in 1811.

Rosanna Pettibone Wilcox, or the widow Wilcox as she was known, passed away on Oct. 15, 1813, at the age of 75. She is buried alongside her husband and her infant son in Center Cemetery. On June 23, 1815, the house and property were granted to the three children, and her son Ezekiel then purchased the property from his sisters for $600, the equivalent of roughly $11,000 today.

The Wilcox Tavern era came to an end on May 4, 1815, when the property was sold to Ephraim Coy.

This is the first of two articles on the history of the Wilcox Tavern and the second of a series of articles on 18th-century Norfolk houses. To date, close to 50 have been identified, spread over Norfolk’s 46.4 square miles.