Trees, Time and Change on the Village Green

By Ted Hinman

The town green is Norfolk’s symbolic center, and it has a long history as a meeting place for community events. On the green, the people of Norfolk honor their fallen and celebrate the seasons. For at least 260 years, we have also marked the passage of time as trees grew and were replaced because of old age or disease.

The first mention of tree planting on the green came in 1778 when it was noted that elms were planted. A decade later came more elms and buttonwoods (sycamores). In 1791 more large elms were planted, but a mere 18 years later, the green was plowed up and leveled.

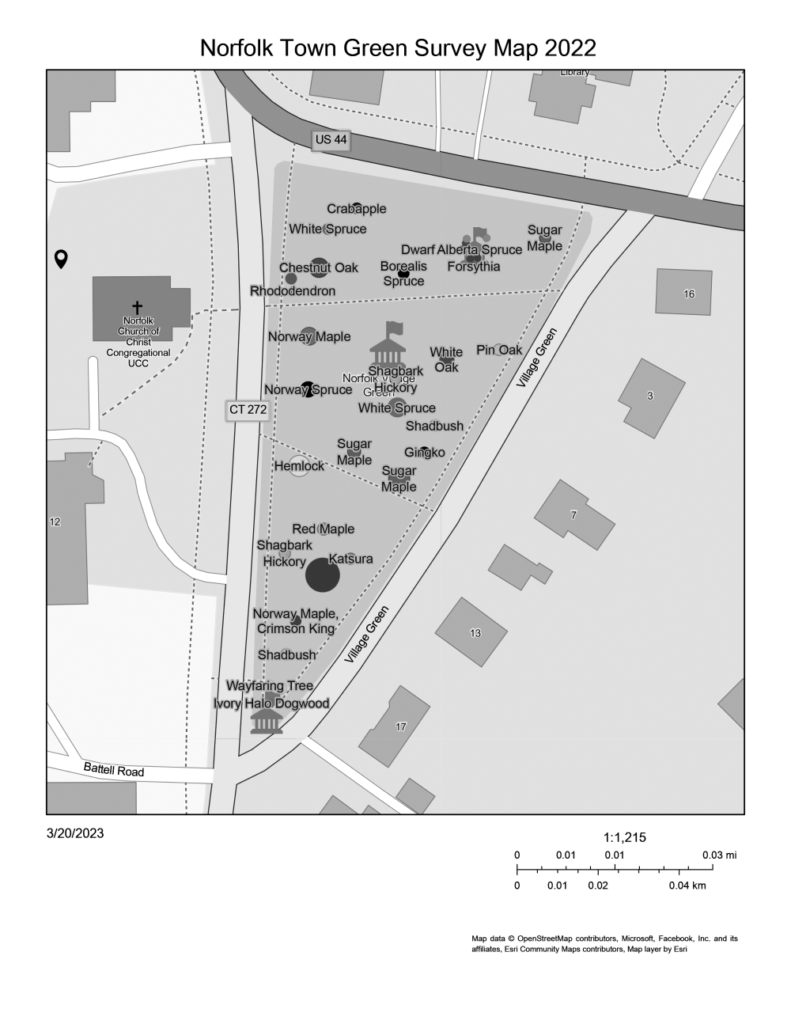

We can look back at this history because people have taken the time to record the numbers and types of trees on the green. We have maps from 1911, 1969 and 1985, and a new one from 2022. We also have a book about the green, written in 1917 by Dr. Frederic S. Dennis of Dennis Hill fame, and also Crissey’s history of Norfolk.

William Rice, described by Dennis as the “beloved schoolteacher,” started a program in 1850 to populate the green with all the native trees of Norfolk. Since our first map is from 61 years later, can we guess which trees he chose?

Some trees from the 1850s have survived, based on our four tree maps. The tulip tree in the green’s south end, which was planted by Rice after it was “brought on his shoulder from West Norfolk,” is now five feet in diameter. The chestnut oak in the northwest corner probably dates from the 1850s, and perhaps the larger sugar maple along the path crossing the green as well. Those trees are 173 years old and look better than any of us at that age.

The 1911 map shows the green crowded with trees: 26 elms were planted along the edge of the green, and the interior was also thick with trees, for a total of 62. Many of these 1911 trees did not survive. The butternuts, chestnut and tamarack were all gone by 1969, and the elms had begun their slow die-off.

The next map, created by Darrell Russ in 1969, shows more varied species. Some elms remain, but exotics have also been planted: gingko, concolor fir, Norway maple. Interestingly, the ginko across from the Historical Society is a female (which produces fruit with a vomitous smell), whereas the tough trees that thrive in cities are usually males. The 50 trees and shrubs recorded in 1969 include more sugar maples and Norway spruce than previously. The 1985 survey was again compliments of Darrell Russ, and the tree count came down again, with only 44 trees and shrubs recorded. Included is a white oak to the east of the Civil War monument which Russ describes as a Bicentennial White Oak. These are descendants of the Charter Oak in Hartford, which lived about a thousand years and crashed down in a storm in 1857.

My survey, conducted in the summer of 2022, shows 35 trees. The green has more nonnative trees now, and the old Christmas tree has been replaced with a newer, small tree. There is plenty of sunny space. Our trees still face threats like the spongy moth, the hemlock wooly adelgid and the new pathogen, beech leaf disease. But there are now disease-resistant elms that could return to the green, and we may soon have a genetically engineered chestnut to plant.

The trees on the village green will continue to change and adjust to the world, as well as providing us shade as we catch our breath after the annual road race. A messenger from the past, the 173-year-old tulip started to grow when the town was still young, and it was part of someone’s vision for the future. Old age, disease, insects and extremes of climate will continue to cull trees and open space for planting. Perhaps that will give future generations the chance to fulfill William Rice’s vision of planting only native Norfolk trees. We can let them fight over that.

I have created a website that displays the four maps of the trees on the green: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/faa2229406cd4390ac938fa3fbd7edbd.