How Crowdsourcing by the People is Putting History Online

Text By Kelly Kandra Hughes

Photos Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Betsy Garside, a resident of New Mexico with deep family roots in Norfolk, attended many of the Norfolk Library online events throughout the Covid-19 pandemic. She found them “a way to go somewhere fun,” whether it was an authors talk, a Friday afternoon chat via Zoom with the Norfolk Knitters or a virtual visit to faraway Croatia or Spain. Little did she know that one program in March 2021 would significantly change how she would spend her time during the pandemic.

The program featured New York Times bestselling author Janice P. Nimura discussing her most recent book “The Doctors Blackwell: How Two Pioneering Sisters Brought Medicine to Women and Women to Medicine” (2021, W. W. Norton & Company). During the Q&A, Nimura answered an audience question about the original source materials used in her research. She explained that she found many pieces in the Schlesinger Library at Harvard University, as well as at the Library of Congress (LOC). She added that the LOC was seeking volunteers to transcribe the original documents in the Blackwell collection so they could be accessible to everyone.

“There’s something spine-tingling about deciphering a crumbling letter and hearing someone’s voice across the centuries,” says Nimura. “And especially the voices of women, so much less often preserved in the historical record.”

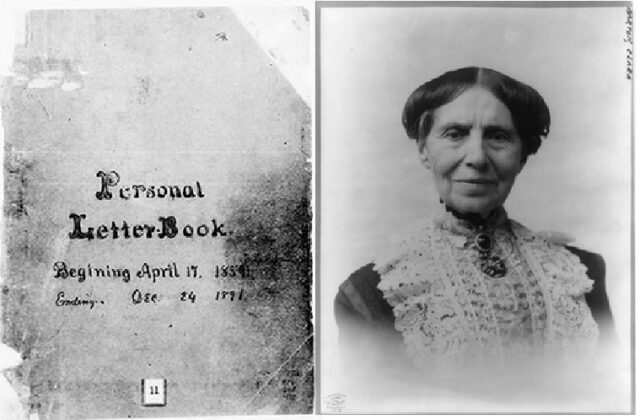

“What a cool idea,” thought Garside, sitting in the virtual audience. She checked out “By the People,” a crowdsourcing project started by the Library of Congress in 2018 at crowd.LOC.gov and—flash forward six months—has now transcribed 118 pages for the LOC, including Walt Whitman’s war journals, Clara Barton’s letter books and Theodore Roosevelt’s correspondence. She’s right there with Nimura on how powerful the transcription experience can feel. “These are often hand-written documents from people who shaped America.”

Even though Garside has a deep history with transcription—her University of Pennsylvania honors thesis involved the transcription of the years 1760-1780 in a diary from the Haverford College Quaker & Special Collections—she believes anyone who is interested in transcribing for the LOC can get involved right away. “They make it so easy. You sign up, which is literally just giving them your name and email, or you can jump right in and start transcribing.”

The process is relatively straightforward. The LOC has documents organized by campaigns. Some currently available for transcription are “Clara Barton: Angel of the Battlefield”; “Presidential Papers at the Library of Congress”; “Suffrage: Women Fight for the Vote”; “The Blackwells: An Extraordinary Family”; and “Rough Rider to Bull Moose: Letters to Theodore Roosevelt.” A transcriber selects a campaign, then a document. A scan of the original document pops up on the left side of the screen and a blank text document on the right, along with an encouraging note from the LOC to “Go ahead, start typing. You got this!”

For people who may be interested in transcribing, but worry that they might make a mistake, the LOC has a solid system of checks and balances in place. The crowd-sourced transcriptions are reviewed several times by registered reviewers; by the time the final transcription gets to a LOC librarian, it’s a clean document.

Garside is grateful for the opportunity to connect with the past this way during a time that’s been filled with anxiety and uncertainty. “It’s an escapist thing to do… to dig in and figure out a four-page letter someone sent in 1860. It’s a lovely picture of the past, but it’s also a nice sort of way to get some perspective on the present.”

Nimura appreciates the work that Garside and other transcriptionists have done for the sake of history. “A published (and polished) memoir is one kind of record, but an angry rant to a little brother or a gossipy note to an older sister is more revealing,” she says. “I’m thrilled that Betsy has joined the ranks of archival treasure-seekers and is helping make these documents more accessible to those who don’t love 19th-century handwriting as much as nerds like me.”

As for the documents in the Blackwell family collection: yes, Garside did work on this campaign. To her delight, she even found a family connection in a fundraising letter to Alice Stone Blackwell, Elizabeth Blackwell’s niece. The letter had been sent to Alice Blackwell in 1949 from the Committee of 100 in New York. Along the letterhead’s left-hand side was printed the name of Mrs. Richard S. Childs, Garside’s great aunt. “Such a surprise!” exclaims Garside. “It was sort of everything swirling together, different generations and different connections.” She also thinks it’s only a matter of time before she comes across another surprising connection. “Even a hundred years ago America was a much smaller world. If I’m digging around in the past, my chances of stumbling on something interesting or another connection seems highly likely.”