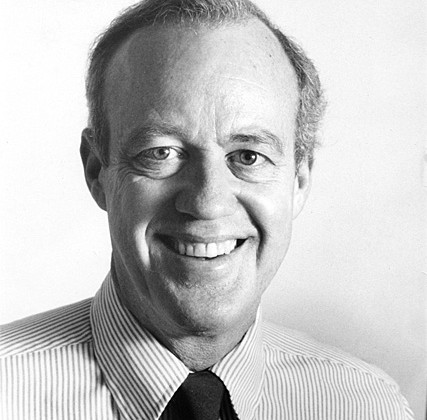

Lloyd Garrison, Founding Editor of Norfolk Now, Dies at 83

By Wiley Wood

Lloyd Garrison, a journalist, editor and Norfolk presence for the past 18 years, who covered Europe and Africa for The New York Times in the 1960’s and in retirement founded this newspaper, died at his home in Norfolk on June 21. He was 83 years old.

The cause was complications of prostate cancer, according to his family.

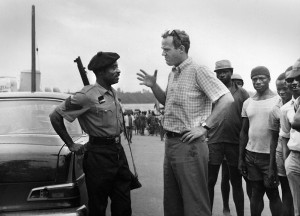

At a time when media coverage of Africa was thin and its wars distant and confusing conflicts, Garrison gave them a human face. Stationed in Leopoldville, Congo in the mid-1960’s, he accompanied a small rebel force across the border into Angola, hiding from Portuguese patrols, wading across rivers, pushing through the rainforest to reach a clandestine rebel base and bring food to refugee camps. Garrison’s portrait of the young rebel commander, published in The New York Times Magazine, took pains to show the discipline and competence of this “totally self-made army, African trained, African staffed, African led.”

Later in that decade, based in Lagos, Garrison charted the growing tensions that led to the Nigerian civil war and the secession of Biafra. Once again, he reported largely from the side of the insurgents, flying into blockaded airstrips under cover of night to conduct interviews with the Oxford-educated Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu, “brooding, detached and sometimes imperious,” who led his countrymen into a brutal and protracted war. But Garrison also talked with the ordinary Biafran, whose message of rage and defiance against the corruption of the post-colonial government and whose grim hope for a better future he conveyed to Americans.In 1968, now living in Paris with his young family, Garrison covered the Winter Olympics in Grenoble, the Vietnam peace talks, the armed clashes in May 1968 between students and riot police, the occupation of factories by workers in industrial Brittany that eventually toppled De Gaulle, the Cyprus conflict between Greece and Turkey, a middleweight title fight in San Remo, Italy—all the while hopscotching back to Biafra on Red Cross planes to report on the famine, whose images of distended bellies and stick-thin children had gripped the West’s attention.

His articles from that period open vividly and analyze the circumstances shrewdly; they bristle with quotes from big men and little and shine with human sympathy.

Covering the middleweight bout between the champion, Nino Benvenuti, and Don Fullmer, Garrison describes Benvenuti as “a raven-haired glamour boy, handsome enough to appear in television commercials.” Fullmer, who lost the match, was glumly at lunch with his entourage when Garrison found him the next day: “His face was a portrait of a loser. His eyes were all but puffed shut, and the stitches stood out like chicken wire where the doctor had shaved his eyebrows to get at the shredded tissue beneath.” In the rueful banter that follows, Garrison captures both the man’s pain and his grace in defeat: “I got no one to blame but myself.”

Lloyd McKim Garrison was born in New York City in 1931. A lineal descendant of the abolitionist and editor William Lloyd Garrison, he grew up in Madison, Wis., where his father, Lloyd K. Garrison, was dean of the University of Wisconsin Law School, and in Washington, D.C., where his father moved during World War II to chair the National War Labor Board.

Already considering a career in journalism when he graduated from Milton Academy in 1950, Garrison worked that summer on a kibbutz in Israel, then parlayed his acceptance to Harvard into a freshman year at the American University of Beirut as a special student in Arab Studies. While at Harvard, he worked part-time on night rewrite at the Boston bureau of United Press. He landed his first job after graduation as a news writer at NBC News in New York and, aside from a two-year stint in the military, continued to write for television and radio through the 1950’s. It was during these years that he first courted his future wife, Sarah Crocker, a teacher in New York.

By 1960, Garrison had decided to switch to print journalism and went to Africa to try his hand at writing freelance articles. He sold stories to the Reader’s Digest and The Saturday Evening Post, was hired by Newsweek, then The New York Times.

On the eve of another trip to Africa, Garrison proposed once more to Sarah Crocker. According to their daughter, Katharine, he said, “Again, will you marry me?” The young woman heard that he was leaving for two years instead of two months. The next day, she said yes.They married in 1960 and went to Leopoldville for their wedding trip. “It was meant to be a working honeymoon,” said Garrison in a 2008 interview.

In 1961, the couple settled in Washington, D.C., where Garrison covered the first year of the Kennedy administration for The Times. He filed stories on the civil rights movement, segregation in Maryland, Martin Luther King’s plea to President Kennedy to end the race laws, and Adlai Stevenson, then the U.S. delegate to the United Nations.

Starting in 1962, Garrison worked as a foreign correspondent for The Times, opening its first Africa bureau and serving for several years as the paper’s senior correspondent in Africa. Filing from Leopoldville, then Lagos and later in the decade, from Paris, Garrison won eight New York Times Publisher’s Awards.

In 1970, Garrison returned to New York City with his family and resigned from The New York Times to write a book on Africa. Although he worked on it for most of a decade and his editor at Simon & Schuster was enthusiastic about the manuscript, the book was never finished. Garrison lectured on modern African history at Yale and filled in as a newscaster on Channel 13, New York City’s public television station, during the yearlong newspaper strike of the late 1970’s. In his forties, he started competing in marathons.

He struggled with alcoholism, then overcame it, returning to mainstream journalism as a staff writer at Time magazine in the mid-1980’s. He then moved to the UN, where he started a bimonthly magazine for the United Nations Development Program, and his last job before retiring was at the Ford Foundation, where he served as director of communications and launched a similar magazine. “What I remember from his years at the UN and Ford,” said Katharine Garrison, “are the holiday parties he would give each year. Everybody was invited from the secretaries on up, and young writers were always giving toasts to Lloyd for mentoring and encouraging them.”

In 1996, Garrison moved with Sarah to Norfolk, Conn., where he built a house looking out across the Litchfield Hills. It was a good place for children—with its pond, its trails snaking through the woods, well-groomed and color-coded, its treasure tree, its rectilinear woodpile, and always a frisky Lab or two. The Garrisons divided their time between Norfolk and a house in North Haven, Me.In 2000, convinced that every town needs a paper, he began to raise money and support for a nonprofit monthly with cofounder Rosanna Trestman. Norfolk Now is currently in its twelfth year of operation.

“Norfolk Now was like his baby,” said his son Ben Garrison. “He saw the paper as a way to bring the community together—a bridge between new and old residents alike.”

Garrison retired from actively editing Norfolk Now in 2008 and turned increasingly to making the paper a player in community affairs. When the town’s first selectman was challenged in the elections of 2009, Norfolk Now sponsored debates between the candidates. In 2013, the paper hosted a conference on the future of small towns in rural Connecticut. Garrison was the driving force behind both events.

When not working on the paper, Garrison loved to spend time sailing in Maine, attending the Meeker Colorado Dog Trials and skiing in the West and at Butternut. “He went until he could go no more,” said his oldest son John. “Graceful, caring, never complaining, that is how we will remember him—a big heart.”

Lloyd Garrison is survived by a sister, Ellen Shaw Kean, of Concord, Mass.; his two sons, John, of Rockville, Md., and Ben, of Maplewood, N.J.; his daughter, Katharine, of Montclair, N.J.; and seven grandchildren. His wife, Sarah Crocker Garrison, died in 2009.

A memorial service will be held in his honor at the Church of Christ Congregational in Norfolk, Conn. on Saturday, September 13, 2014 at noon. In lieu of flowers, the family suggests that donations be made to the Lloyd Garrison Memorial Fund in support of Norfolk Now.

[Checks can be made out to: Norfolk Now dba CSG, with LGMF in memo line, and sent to Norfolk Now, P. O. Box 702, Norfolk, CT 06058.]

The New York Times’s obituary of Lloyd Garrison can be viewed by clicking here.

What the NY Times and Norfolk News fail to mention was Lloyd’s culinary skills. I am a friend from North Haven, ME, and when in June when he came up to get his boat ready and open his house for renters, he would occasionally ask me over for supper. He specialized in bread making, and it was always a delicious meal. He even made me a cappuccino with an automatic “frother” which I promptly went out and bought! He was a good friend. Elinor L. Hallowell