Will the Colebrook Community Survive Regionalization?

By Wiley Wood

What will happen to the Colebrook school building? This was one of the first questions raised at the public hearing in Colebrook on August 11. If the town opts to consolidate its primary school with Norfolk’s and bus its children to Botelle, the building will be left empty. Yet Colebrook will still have to heat it during the winter. Will Norfolk help defray these and other ownership costs?

The building might be used for senior housing, said Chris Johnstone, chairman of the Future Use Committee, which is considering Colebrook’s options in the event of a favorable referendum on September 22. Or it might be torn down, preserving the site as a playground, or leased or used by the town as a recreational facility. In every case it remains an asset of the Colebrook community, and neither Norfolk nor the future regional board has an obligation to maintain it.

And how much would it cost to bring the building up to code? If the referendum goes against consolidation, the building would remain in use. Jay Chittum, Colebrook’s school superintendent, said that there is no immediate obligation to install sprinklers or improve air quality—the building has been grandfathered in as a school—but the cost of modernizing is estimated at $3.5 million.

The length of the bus ride for Colebrook children was clearly an issue for many parents. The regionalization plan puts a cap of one hour on a student’s ride, following the same guidelines as those currently in place, said Jonathan Costa, a consultant to the regionalization study group. And students will be picked up at their driveways, not at neighborhood collection points.

With the schools only six miles apart, the number of buses and their routing are the key factors in determining ride times, said Costa. But these specifics will be decided by the future regional board, as will many other aspects of school operation.

A number of Colebrook residents expressed skepticism about the future regional board, fearing that it might be under considerable pressure to realize savings and therefore not always able to act in the students’ best interests.

But regional systems, a member of the audience pointed out, present their budgets directly to the voters of their constituent towns, rather than seeking approval from the town’s board of finance, as Botelle and Colebrook Consolidated must do.

Another deep current of concern in Colebrook was the effect that losing its school would have on the town. Would Colebrook decrease in population? Would couples with children avoid living there because it had no school? Would property values decline?

Costa suggested that the quality of the education in a region is more closely correlated with economic indicators than the location of its school. Stockbridge, it was noted, has no schools but educates all its children in Great Barrington, providing a nearby example of a school-less town.

While Norfolk and Colebrook are the first towns to have submitted a successful regionalization plan to Connecticut’s board of education in over 40 years, there are many other towns lined up behind them, said Jonathan Costa, towns that also face declining enrollment and squeezed budgets, particularly in the northwest and northeast corners of the state.

The meeting ended with a Colebrook resident thanking the town leaders for their foresight, saying it was a good opportunity to look ahead and work for the benefit of students in both communities. There was no rebuttal, there was no applause.

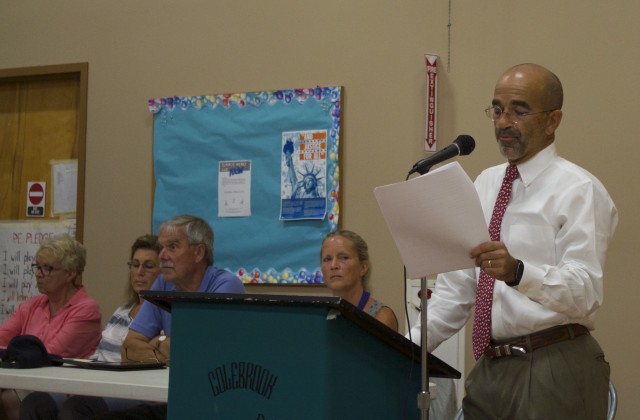

Photo caption: At public meetings in Norfolk and Colebrook, Jonathan Costa walked through the plan to form a new regional district for elementary education in the two towns,, then took questions from the audience. Photo by Wiley Wood.