It’s Only Natural

The Legacy of Glacial Lake Norfolk

By Hans M. Carlson

A couple of months ago I wrote about the low water in Tobey Pond, and how it revealed interesting aspects of the pond’s human history. Today I’m thinking about high water at the pond, and that’s an entirely different story, one which unfolded even before Native people reached this area. You have to go back fifteen or sixteen thousand years to find the high-water mark around here, when most of the northwest part of town was under Glacial Lake Norfolk, and Tobey Pond was still deep below its surface.

Glacial Lake Norfolk formed when the ice retreated to the north and west, at the beginning of the Holocene Era. This began around twenty thousand years ago on Long Island Sound, but did not reach the Litchfield Hills for about five thousand years. Melt water mostly ran south into the ocean, but in a few places where the topography pushed water north, lakes formed momentarily in front of the glacier. This was the case with what is now the Blackberry River basin, when the ice still blocked water from finding its way to the south-flowing Housatonic. The lake only lasted for a brief moment in geologic time, but its legacy is still visible today.

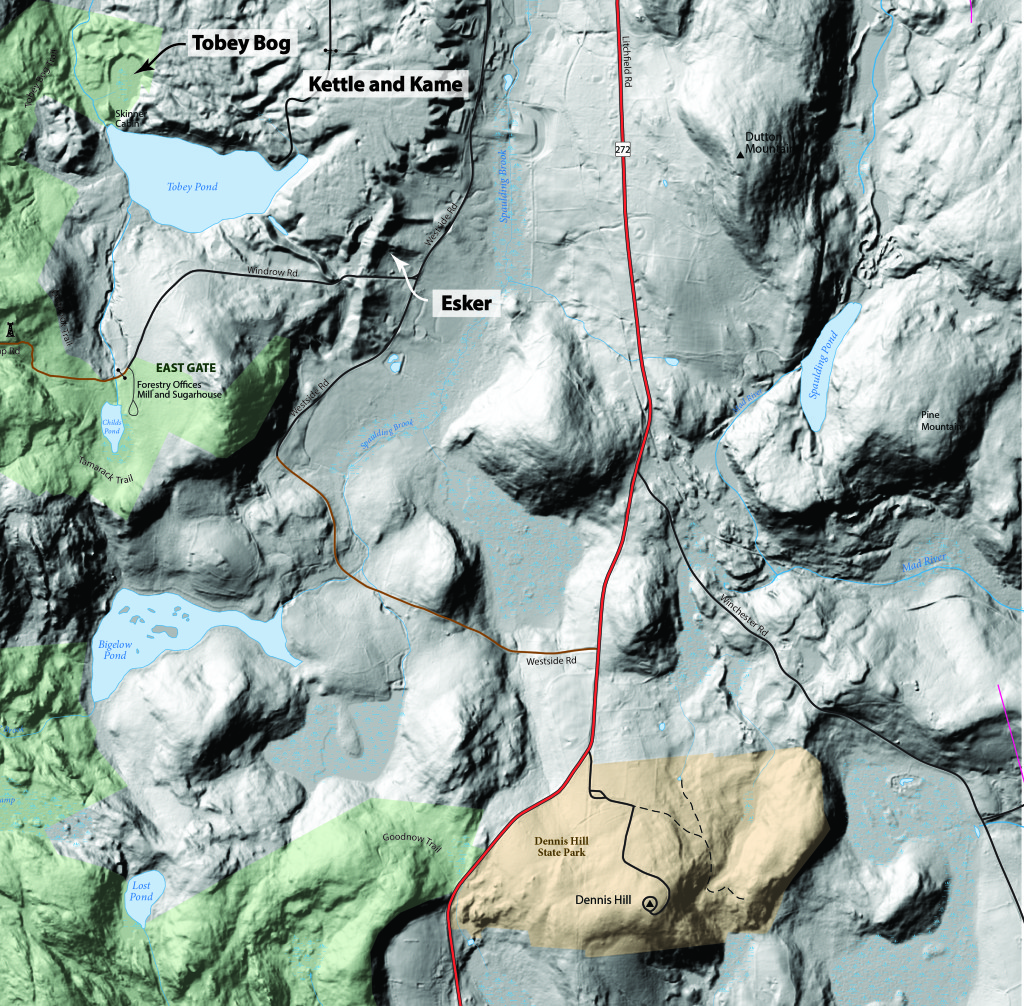

The water not only filled the basin around Tobey Pond, but spread back into the wetlands that are now between Westside Rd and Route 272, probably as far south as Dennis Hill Park. The top of Haystack Mountain might well have been an island for a while too, before the glacier retreated enough to let the water flow by and down into the valley in Canaan. The formation and eventual draining of the glacial lake caused a great deal of erosion and deposition in the basin, leaving us today with very interesting land formations.

There is a beautiful esker – the deposition left by a river under the glacier – between Tobey Pond and Westside Rd. The land there is basically all sand and gravel left from the ancient riverbed. If you walk the road down to Tobey Beach, you can pick out a little of the “kettle and kame” topography to the west as well. Kames are deposits that happen at the melting edge of the glacier, and kettles form when chunks of ice calve off and embed themselves in the soft ground, leaving holes when they melt and drain. The area north of the beach was the site of the old Norfolk Downs golf links, and the post-glacial topography likely made for challenging play.

When a kettle was formed by a big enough chunk of ice, and compacted soils or bedrock stopped drainage, the melt water would leave a body of water, and this is what created Tobey Pond. This was enhanced with the help of the dam at the west end, but Tobey is officially a kettle pond, which are scattered across New England. They become more and more common the further north you go, and if far enough north, then postglacial ponds and lakes are the defining feature of the Canadian Shield.

A couple of hundred yards northwest of Tobey Pond is another kettle, which did not drain or become a pond, and it is a rare thing in this region. Where peatlands are fairly common in northern New England and Canada, Tobey Bog is one of few true bogs in Connecticut. Its floating mat of sphagnum moss – probably more than thirty feet thick – comprises one of the most unique ecosystems we have in Great Mountain Forest in fact.

Bogs form in poorly drained kettles which do not have enough of a watershed to fill into ponds, and thus form closed – or at least mostly closed – systems. Limited input and outflow create a nutrient poor ecosystem with high acidity levels, and this selects for a specialized cohort of plant species that are adapted (sometimes uniquely so) to such harsh conditions. Here is where you find things like carnivorous plants that eat insects to make up for the extremely low levels of nitrogen in the acidic Sphagnum substrate.

From landforms and waterways, down to the level of highly adapted species, the legacy of the glacier and its retreat are everywhere around us. Ice and its aftermath, in fact, were the defining feature in Norfolk long before the town got its nickname.