Scandal and Bribery Tainted State Senate Election of 1856

A Look into Norfolk’s Past

By Ryan Bachman

With 2016 an election year, news stories alleging shady political deals and corruption abound, but stories such as these are nothing new. In 1856, Norfolk was the scene of a political scandal that shocked citizens all over Litchfield County. That spring, tensions over social issues like temperance led to bribery and a fixed election.

Norfolk was then part of the 17th State Senatorial District. In 1856, two Norfolk businessmen were vying for the office of state senator—Samuel D. Northway and Nathaniel B. Stevens. Northway, the elder of the two, ran a tannery in South Norfolk, while the 33-year-old Stevens owned a factory along the Blackberry River. Each candidate was loosely affiliated with an established political party, but disaffected supporters of a relatively new party completely altered the course of the election.

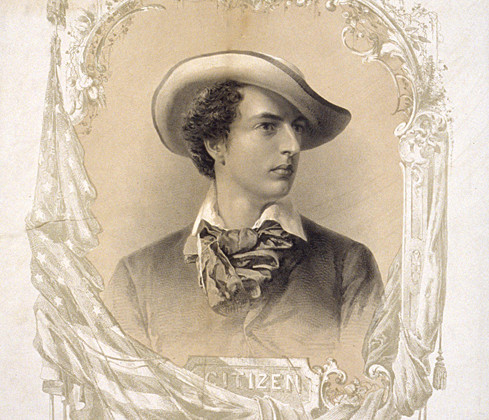

The American Party, better known by its popular nickname, the Know-Nothing Party, began in the 1840s as a secret society. Within a decade, the group had morphed into an organized party and entered mainstream politics at the national level. The central platform of the Know-Nothing Party was devoted to nativist, anti-immigration policies.

Know-Nothings were specifically opposed to the increased number of Catholic immigrants who came to the United States during the mid-19th century, especially those from Ireland. Party supporters argued that it was impossible to integrate these immigrants into a society that had historically been dominated by English-speaking Protestants. While immigration reform may have been the main goal of the Know-Nothings, the group also took positions on other social issues of the day, like temperance, in order to widen its appeal.

Temperance was the issue that ultimately led to charges of voter fraud in Norfolk. Although some Norfolk citizens undoubtedly shared Know-Nothings’ views on immigration, both Northway and Stevens employed Irish workers and were unlikely to support restrictions on immigration. In the absence of such nativist opinions, local Know-Nothings instead vetted each candidate on their support for the temperance movement, which called for limiting the sale and consumption of alcohol.

Efforts toward temperance grew partly from concerns over alcoholism that accompanied the shift toward an industrialized economy. Drinking had always been a part of American life, but low-priced, mass-produced liquor and the harsh conditions of many early factories had led to increased alcohol consumption.

Norfolk was well known as an active temperance community. For a brief period during the 1840s, shopkeepers were required to keep registries of their customers who purchased alcohol. Over time, however, many town residents increasingly came to resent temperance practices that interfered in their personal lives. Young people, and more recent arrivals to Norfolk, were particularly unenthusiastic about the temperance movement by the mid-19th century.

Two years before the election of 1856, the state legislature passed a law that cracked down on the production of alcohol, but Norfolk Know-Nothings wanted even stricter legislation that would ban all alcohol not sold for medicinal purposes. After researching the two state senatorial candidates, the Know-Nothing Party concluded that Stevens was too weak on the issue and officially endorsed Northway, but the party was soon disappointed to find that their endorsement of Northway did nothing to increase his popularity. On the contrary, the approval of the nativist, pro-temperance party apparently hurt his campaign.

As the Know-Nothings watched their endorsement unintentionally sabotage their preferred candidate, party leaders scrambled to brainstorm a new strategy. Above all, the Know-Nothings wanted to defeat Stevens, so members of the party settled on a desperate new plan to elect Northway—they would simply bribe voters on Election Day. Ironically, the Know-Nothings decided that the most effective bribe to offer voters was not money or political favors, but rum. And it worked.

In March of 1856, Northway was elected state senator. Inevitably, word of the scandal reached the press and shocked readers throughout the county. One Canaan resident lamented that such an event had occurred in “Old Norfolk,” the “banner town for morals and temperance.”

Despite the blatant voter fraud, no action was taken to address accusations of bribery, and state authorities allowed Northway to serve out his term. As for the Know-Nothing Party, news of the scandal helped hasten its decline in Norfolk. After 1856, it never regained its former level of influence, and the party had disintegrated at the national level by the onset of the Civil War.

Illustration: Print from the Library of Congress entitled “Uncle Sam’s youngest son, Citizen Know Nothing.” Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.