A New England Pastor, a Dutch Classicist and a Roman Stoic in One Book

Treasures From the Rare Book Room

By Lucy Mookerjee

The Norfolk Library’s rare book room holds the collections of the library’s earliest donors.

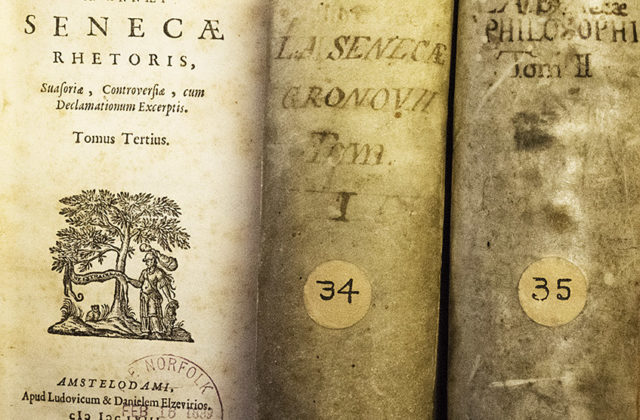

Plenty of Norfolkians know a rare bird when they see one. But many birders would be hard-pressed to identify the markings of a “rare” book. What makes a rare book rare? It depends—age, scarcity, market value. Whether you’ve spotted it or not, the Norfolk Library has an entire room devoted to rare books. Like rare birds, several of them are not—at first glance—beautiful. They are not gold-stamped, leather-bound sets of Dickens. They perch unassumingly on shelves in a temperature-controlled room. One of the most remarkable items here is the least remarkable looking: a three-volume set of the works of Seneca, annotated by the 17th-century Dutch classicist Johann Gronovius. Despite its lack of pretty plumage, this edition of Seneca (originally collected by Azariah Eldridge, a man of letters, pastor of the Congregational Church,and patriarch of one of Norfolk’s founding families) happens to have been a best seller in its time.

All three volumes have original vellum bindings. Their rough pages—made from vats of rotted rags—bear the impression of chain lines from the paper molds on which they were stretched. The title pages feature Athena, goddess of wisdom, holding a banner that reads: “Ne extra oleas” (Nothing but the olive), the motto of the Brothers Elzevier, who printed the volumes in Amsterdam in 1648. Even if an original title page had been replaced with a later one (as happens to be the case with Volume 1), it would still be possible to gather information abut when and where the book was produced by studying its physical characteristics. (The question of “why” a title page might be removed and replaced is another story altogether.)

Pasted inside the cover of each volume is Azariah Eldridge’s presentation label. This piece of provenance is puzzling. When Eldridge’s edition was given to the library in 1889, the books were already 200 years old. Like Eldridge, Gronovius was a scholar. He is credited with having rescued the Stoic philosopher from the decay of late antiquity. Does the presence of his best-selling volumes in Eldridge’s collection betray the reverend’s passion for philosophy or his passion for collecting?

On the shelf, these 17th-century volumes seem almost insignificant.

The Netherlands of the 17th century was the hotbed of the European book trade. The demand for books was so great (and the regulations so few) that printers took to printing in bulk, sometimes pirating editions of foreign best sellers before they hit the international market. In a move that has vexed bibliophiles for centuries, the Elzevier brothers appropriated a French small-book format known as the duodecimo (so-called because it was originally made by folding and cutting a sheet of paper into 12 leaves) to print affordable, portable “classics.” Just as Gronovius foresaw the importance of compiling ancient doctrines before the artifacts of ancient Greece had been excavated, the Elzeviers spotted the 12mo as a low-cost solution to an international interest. Pirated? Perhaps that explains the replacement title page. Rumor has it that the Elzeviers had spies in Parisian printing houses. Before long, however, complaints about indecipherably tiny type prompted them to abandon the 12mo “classic.” The moment they halted production, the Elzevier 12mo became a hot-ticket item.

Seneca maintains that the wisdom of the individual leads to perfection. Azariah Eldridge may have been keeping up with the Joneses by collecting the “Elzevier 12mo,” but it is easy to imagine that the leader of a church that espouses “the right of individuals to interpret religious principles” collected these books for “nothing but the olive”—to keep in his pocket, not on his bookshelves. It’s worth noting that Gronovius dedicates his edition to Queen Christina of Sweden (1626-1689), a classicist, collector and controversial figure who championed the “individual interpretation” of religious orders and women’s rights, abdicating at the height of Sweden’s power during the Thirty Years’ War. Soon afterward, in the summer of 1754, this rare 17th-century bird paid a visit to Gronovius in Hamburg. Age, scarcity, value, romance—you can’t put a price on this stuff.

Photos by Bruce Frisch.